Three decades on and families still seek justice for murder of six innocent loved ones

Three decades on and families still seek justice for murder of six innocent loved ones

19 June 2024

ON the morning of Saturday, June 18, 1994, few outside of Co Down had heard of Loughinisland.

That night Loughinisland made international news after one of the most heinous attacks of the Troubles.

The Heights Bar was packed with men of all ages who had just watched the Republic of Ireland humble Italy 1-0 in the World Cup.

Just after 10pm, two men walked into the bar. They were both wearing boiler suits, with one armed with a high powered Vz. 58 Czechoslovakian assault rifle.

While one held the door open the door, the gunman opened fire in deliberately aimed bursts, singling out those trying to escape.

One man was shot a number of times as he bolted for the toilets. The gunman then turned his attention to those who had nowhere to run.

When the assailants left after just a few minutes, five men lay dead – Adrian Rogan (34), Malcolm Jenkinson (52), Eamon Byrne (39), Dan McCreanor (59) and his uncle Barney Green (87), the oldest victim of the Troubles. Thirty five year-old Patsy O’Hare later succumbed to his injuries on his way to hospital. All the victims were innocent Catholics.

Five other men were injured – Aidan O’Toole, son of the bar owner, Brenny Valentine and Anthony Milligan, all from Loughinisland, Colm Smyth, from Drumaness, and Brian McLeigh, from Annadorn.

The killers escaped with their getaway driver in a red Triumph Acclaim, which sped towards Annacloy and was found by police off road near Saintfield the next day.

On August 4, the rifle used in the attack were found hidden at a bridge near Saintfield along with a hold-all containing boiler suits, balaclavas, gloves, three handguns and ammunition.

The first arrests were made on July 18, a month after the attack, when six men were scooped as suspects under the terrorism laws. Two of them were re-arrested on August 22, along with a further suspect, but all were later released without charge.

The killings left the community in shock and there was an outpouring of grief.

While Loughinisland was aware of the Troubles, it was always a community removed from the violence that had plagued the rest of the province for over 25 years.

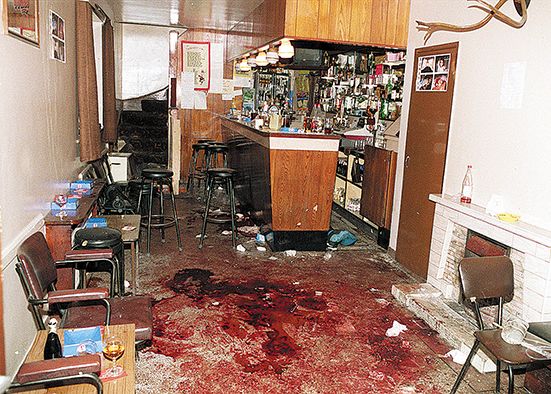

One of the first ambulance crew members to arrive at The Heights Bar said it was one of the worst scenes he had ever seen in his career and described the atmosphere as “cold and eerie”.

The first priest to arrive at the scene was Canon Dominic McHugh, from Crossgar. He was joined by Loughinisland parish priest Canon Bernard Magee. Both clergymen administered the last rites to the dead.

“The scene inside the bar was the most gruesome sight I have ever come across,” Canon McHugh said at the time.

“There were bodies piled on top of one another just inside the doorway and it was clear the men had died where they had fallen.”

In the immediate aftermath of the killings, the police vowed that they would pursue every lead possible into finding the killers.

At the time, detectives said that the nature of the attacks “narrows it down to just a handful of men with the cold-blooded experiences to leave just four out of 15 customers uninjured”.

The police believed that the attack was carried out by members of the East Belfast UVF and were assisted by assailants who had “intimate knowledge” of the backroads.

The loyalist terrorist group claimed that there had been a republican meeting taking place at the pub at the time of the attack, but this was quickly dispelled by the police who labelled it as a gruesome sectarian attack.

The loyalist terrorist organisation also claimed the attack was a retaliation for the killing of three UVF members on the Shankill Road in West Belfast by the Irish National Liberation Army two days previously.

The then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Sir Patrick Mayhew, said that the RUC would not give up until the killers were caught and that the people who carried out the attack would spend many years in prison.

The families of the victims had faith that the police would arrest and charge the perpetrators at the time. The victims were well-known to some of the officers and police had already found the getaway vehicle.

Even in the wake of such a terrible tragedy, the community of Loughinisland showed its compassion to the nine children and four widows who had been left to mourn their loved ones.

Having always been a community of tolerance and understanding, where Catholics and Protestants lived in peace and harmony, the whole community rallied behind the families, determined not to be embittered by the evil act that had befallen the village.

As echoed by Fr Con O’Reilly who during the joint funeral of Mr Green and his nephew, Mr Dan McCreanor, told mourners that “such darkness is foreign to this community of peaceful and loving Catholic and Protestant people”.

Thirty years after the horrendous attack and police assurances, the campaign for justice is still ongoing, led by the families of the victims as no-one has been charged with the murders.

In the days after the attacks, officers assured Clare Rogan, the widow of Adrian Rogan, that they would leave ‘no stone unturned’ in their quest to find those responsible for the attack.

The families of the victims sought legal representation over fears of how the police the handled the investigation.

In March 2006, the families lodged an official complaint with the Police Ombudsman amidst allegations of police collusion following claims that the getaway car had been supplied to the gunmen by a RUC agent.

The complaint included allegations “that the investigation had not been efficiently or properly carried out, no earnest effort was made to identify those responsible, and there were suspicions of state collusion in the murders”.

It was alleged that police agents or informers within the UVF were linked to the attack, and that the police’s investigation was hindered by its desire to protect those informers.

The victims’ families also alleged that the police had failed to keep in contact with them about the investigation, even about significant developments.

It was revealed that the police had destroyed key evidence and documents. The car had been disposed of in April 1997, ten months into the investigation.

In 1998, police documents related to the investigation were destroyed at Gough Barracks RUC station, allegedly because of fears they were contaminated by asbestos.

It is believed they included the original notes, made during interviews of suspects in 1994 and 1995.

A hair follicle had been recovered from the car but nobody had yet been charged, while other items such as the balaclavas and gloves worn had not been subjected to new tests made possible by advances in forensic science.

A key eyewitness claimed she gave police a deion of the getaway driver within hours of the massacre, but that police failed to record important information she gave them and never asked her to identify suspects.

A serving policeman later gave the woman’s personal details to a relative of the suspected getaway driver. Police then visited her and advised her to increase her security for fear she could be shot.

In 2008, it was revealed that since the shootings, up to 20 people had been arrested for questioning but none had ever been changed.

After more evidence was revealed, the Police Ombudsman’s office announced a report into the killings would be published.

Led by then Police Ombudsman Al Hutchinson, the report was published on June 24, 2011. It said that the police investigation had lacked “diligence, focus and leadership, that there were failings in record management, that significant lines of enquiry were not identified, and that police failed to communicate effectively with the victims’ families.

It said that there was “insufficient evidence of collusion” and that there was “no evidence that police could have prevented the attack”.

The report received scathing criticism. Mr Hutchinson had controversially used his own definition of collusion to produce his report and acknowledged the families of those killed and injured still believed there was collusion.

“I acknowledge the families belief and while there is reason to be suspicious over certain police actions, I consider there is insufficient evidence to establish that collusion took place.”

Solicitor Niall Murphy described the report’s findings as “timid, mild and meek”.

He added: “The ombudsman has performed factual gymnastics to ensure there was no evidence of collusion in his conclusion.”

The report also made no reference to Special Branch and portrayed the RUC as incompetent instead of pursuing inquiries to would underpin collusion.

After the report’s publication, there were calls for Mr Hutchinson to resign and the victims’ families began a High Court challenge to have the report’s findings quashed.

Mr Hutchinson was replaced by Dr Michael Maguire as the Police Ombudsman, who ordered a new inquiry into the massacre.

Dr Maguire’s report, published in June 2016, produced the most definitive account of the massacre. His 160-page report – Hutchinson’s was just under 70 pages – looked at what happened before, during and after the attack and his findings make shocking reading.

Despite finding no evidence that the RUC knew about the attack and could have prevented it, Dr Maguire nevertheless ruled that there was significant collusion in the case.

Beginning his probe back in 1986 with the attempted murder of a TV engineer near Dundrum by a fledging UVF gang, Dr Maguire’s report roamed across decades.

He concluded that the police colluded with the killers by:

Failing to robustly disrupt the activities of the UVF gang which began operating in South Down in 1986 and was involved in a series of murders and attempted murders in the run up to Loughinisland

Special Branch failed to share intelligence with detectives about the gang and other matters with a “hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil” approach

Special Branch had full knowledge of plans by loyalists to import weapons from South Africa and Israel which arrived in 1987. Some of those weapons were recovered, but others got into the hands of terrorists, including the assault rifle carried by the gunman in The Heights Bar

Within 24 hours of the murder, detectives were given the names of suspects Special Branch believed were involved in the attack but waited weeks before arresting them Police received information that a police officer tipped off suspects were about to be arrested but did not investigate the information

The overall police investigation had elements of “poor professional judgement and practice, if not negligence”.

“Many of the individual issues I have identified in this report, including the protection of informants through wilful acts and the passive turning of a blind eye, fundamental failures in the initial police investigation and the destruction of police records, are in themselves evidence of collusion,” Dr Maguire said.

“When viewed collectively, I have no hesitation in saying collusion was a significant feature of the Loughinisland murders.”

To this day, nobody has been arrested for the murders. Thirty years after the atrocity, the families of the victims’ are still waiting for justice to be delivered.