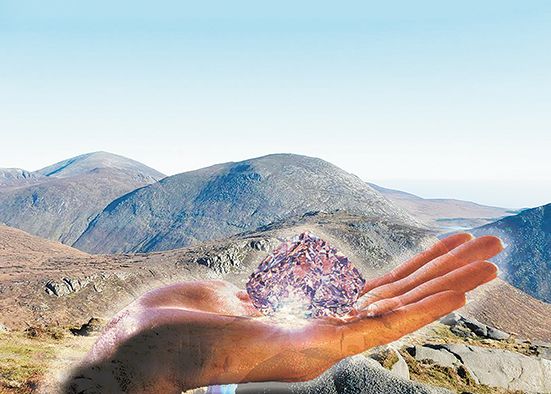

Mourne Diamonds treasures can be found if armed with knowledge how they formed

Mourne Diamonds treasures can be found if armed with knowledge how they formed

8 February 2023

VALENTINE’S Day is around the corner again. That means flowers, jewellery and maybe even marriage proposals.

Cost of living crisis or not, cash will likely be thrown at expensive foreign gemstones. But how many people realise that they could instead find free ‘diamonds’ in our Mourne Mountains?

Hikers and historians aren’t the only people captivated by the Mournes. Plenty of geologists are gripped by the glacial activity that carved the mountains. Folklorists have a healthy obsession too, as do conservationists and wildlife watchers.

Then there are the mineralogists. Those who study and collect rare minerals have used the Mournes as a personal and professional playground since the early 19th century. But to understand why, we must go back even further.

The story starts about 50-60 million years ago and centres around a rock that everyone has encountered if they have ever set foot in Co Down’s famous mountain range.

Mourne granite was formed millions of years ago from the same volcanic activity that shaped the Giant’s Causeway. But rather than spitting lava and ash, all this activity took place deep under the earth’s surface, unnoticeable to anyone or anything on top.

Back then, the entire area was covered by several thousand feet of sedimentary rocks – mainly a type known as Silurian Shale, which is still observable across most of Co Down. Beneath this shale expanse was a cauldron of fiery activity and molten magma. As it gradually cooled over time, it crystallised and hardened. It transformed into granite.

Then, as subsequent centuries passed, huge ice sheets scraped over the earth’s surface, stripping and eroding the soft shale as they moved. In some places, this left only the much harder, more resistant granite landscapes, like those we know today as the Mourne Mountains.

Whether the rounded mounds of Donard and Commedagh, or the rocky tors of Bearnagh and Binnian, they all originate from the cooling of that underground cauldron. Understanding this activity is key to understanding why ‘diamonds’ are found among the Mournes.

Amid all of the subterranean volcanic activity, there were five periods when molten granite was forced upwards into the softer shale above it, known as ‘intrusions’. This is why there are five variants of granite found in the Mournes, named G1–G5. They are all broadly the same age, especially when using a timeline involving millions or years, and they generally share common properties.

In the eastern Mournes, or the High Mournes, G1 to G3 make up the main peaks like Donard, Commedagh, Bearnagh and Binnian. In the western Mournes, which is the area not enclosed by the Mourne Wall, G4 and G5 are dominant. Here, there were longer intervals between the intrusion of magma and its cooling, which results in a slightly finer grain (the word ‘granite’ comes from the Latin ‘granum’ meaning grain, because it is grainy to the touch).

G2 is the variant that most of us know, as it forms spectacular tors like those on Slieve Binnian and Slieve Bearnagh – the same ones that inspired CS Lewis to create the race of giants in his Chronicles of Narnia. G2 is also what produces the so-called Mourne Diamonds.

When it was still magma, G2 had bubbles of hot gases trapped in it. Upon cooling, they created cavities, which are called ‘druses’. Within these cavities, gases, vapour and other fluids cooled to form chunks of colourful crystals.

Over subsequent millions of years, as erosion stripped away the shale above the G2 granite, these cavities became exposed. When found today, they generally look like holes, veins or scoops taken out of the rock. Granite workers called them ‘pummy holes’ and ‘diamond races’ because they are lined with the crystals colloquially called Mourne Diamonds.

In the Mournes, there are three main ‘diamonds’ to be found. Felspars are the most common and vary in colour from pink to white. Quartz is also widespread. It is extremely hard and normally found as a grey or ‘smoky’ colour. Its crystals can reach at least an inch or two in length. Mica has also been found and granite, at least elsewhere, can also host beryl, amythest, fluorite, magnetite, peridot, stilbite, topaz and tourmaline.

Chiselling away at ancient granite to find these gems is not necessary – they are generally found in exposed rock litter. The so-called ‘Diamond Rocks’ are the most famous locality. This is a swathe of exposed rock to the east of Hare’s Gap, near the peak of Slievenaglogh and slightly to the west of Slieve Corragh.

But just as granite can be found right across the High Mournes, so too can its diamonds. Anywhere with rock litter or exposed G2 granite will possess these minerals. Examples have been found at the Devil’s Coachroad, which is the deep gully on Slieve Beg – named so because locals believed that the Devil would rise from this path and cause havoc across the world.

Rock litter on the eastern slope of Slieve Donard, in line with Crossone ridge, has also been known as a source of good specimens. Slieve Binnian is another area said to be rich in what mineralogists call ‘drusy cavities’.

The problem for today’s gem hunters is that generations of amateur geologists and keen-eyed collectors have already overturned many of the stones in their hunt for these rare minerals.

Some of the stone men who built the Mourne Wall a century ago also made large collections, and even moonlighted as guides for interested collectors. There are also stories of local men like ‘Diamond Pat’ Doran, who tried to make their fortunes as a commercial mineral dealer trading specimens found at Diamond Rocks.

Although Mourne Diamonds have become a much rarer treasure than in yesteryear, they can still be found if armed with even a basic understanding of the processes by which they were formed over millions of years.

It may be too late to secure a homegrown Mourne ‘diamond’ for this Valentine’ Day, but there is plenty of time to find one if you are planning on a proposal this time next year.