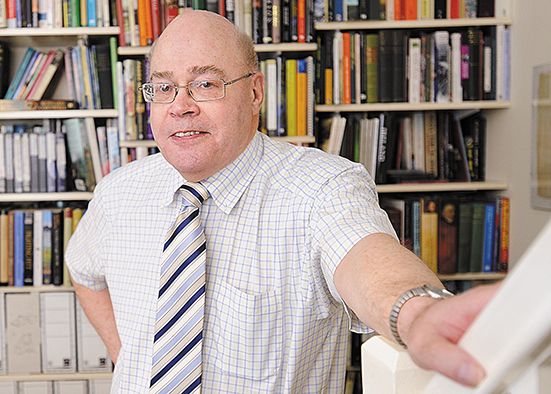

Horace Reid was a man with remarkable talents

Horace Reid was a man with remarkable talents

12 March 2025

BALLYNAHINCH man Horace Reid, one of the foremost local historians of his generation, died peacefully on Sunday, March 2, at Silverbirch Lodge Nursing Home, Saintfield, following a serious illness.

He leaves a written, video and documentary legacy which, at his request, will be distributed to interested groups, and which will be of use and interest to colleagues, students and local history groups for years to come – serving as a permanent reminder of his consummate skills as a writer, researcher and raconteur.

Born Horace Alexander Reid in 1947, the middle of three sons to the late Alex and Sadie, his early years were spent at Ballynahinch Primary School and Down High School, where his studious nature and enquiring mind became apparent.

He excelled in both places, laying the foundations for his entry into Queen’s University Belfast to study English and History, with a further course in Law and Jurisprudence. He seemed destined for an academic career in teaching.

However, in the latter stages of his degree course he developed an interest in health and social care, partially inspired by voluntary work among underprivileged young people in Notting Hill, London. Such experiences radically re-shaped Horace’s outlook on life and future career path, as he re-evaluated how best to utilise his talents for the greater good of society.

In a complete and unexpected departure, Horace applied and was admitted to the Royal Victoria Hospital to train as a nurse. His commitment to this new vocation was total. Whilst all such medical training was a mixture of practical and theoretical, Horace seemed to spend all his ‘time off’ immersed in medical text books. At the end of his course, he was presented with the RVH Nursing Gold Medal, becoming its first ever male recipient.

The two decades of the 1970s and 80s were mainly spent nursing at the Royal. These were amidst the worst period of the Troubles when nursing staff were not only daily confronted with terribly injured patients – which they treated without fear or favour – but personally were subjected to risk as they moved around the hospital complex, in what was effectively a war zone.

Strong bonds were formed among the nursing community during these years, when the importance of mutual assistance was necessary. Those bonds remain as strong today as they were then, with many of Horace’s colleagues among his strongest supporters through his recent illness.

Nursing then, as now, was hugely demanding, and poorly paid. The opportunity to work abroad arose, and he went to work, with other colleagues, at new hospital facilities in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The three years he spent there may have seemed glamorous, but were intense. Still then largely under-developed, there was little to do outside of work, and the searing heat was energy-sapping.

He did manage to arrange some travel: visiting India to see the opulent Taj Mahal, in stark contrast to the surrounding poverty and deprivation.

Horace’s return to the Royal saw him involved in cardiac and fractures specialities, but it soon became clear that all was not well with his own health, marking the onset of an illness which would impact his life and career ever after. At the start his fatigue was attributed to – and almost dismissed as – just a virus. But it was evident that it was more than that.

He had what was eventually recognised as ME (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis), a debilitating disease which renders patients in a near permanent state of exhaustion, unable to function properly.

He was eventually incapacitated and prematurely forced to retire from work. Undaunted, Horace utilised all his acquired medical skills to research the condition, contacted fellow sufferers, and actively lobbied the medical profession and local politicians for support. At this time there was no acceptance that ME was a specific condition: indeed, there was a great deal of official scepticism and resistance.

Horace was widely acknowledged as one of the leading local lights in the campaign for recognition and support for ME patients. He provided much advice and assistance to fellow sufferers as they pursued their own personal battles.

His social life was severely impacted: his life overall was forcibly lived largely within the walls of his house. Occasional necessary trips out were followed by days of exhaustion.

The isolation and periods of forced inactivity were anathema to his eager and enquiring intellect and nature but perversely provided the opening to a renewed interest in historical studies, his first love.

Over the following years, he researched, studied, examined, analysed, prepared records and made notes. He communicated with people of similar interests. Unable to visit public libraries, he built up his own reference library at home. He devoured press articles, filing away and archiving matters of interest.

He was for years an occasional columnist for two local newspapers, the Down Recorder and the Mourne Observer, on matters of local history.

He researched his own family history, going back generations, and as far as photographs could reach, and then beyond. When health permitted, he lectured widely to local historical groups and carried out private research for families and landowners, keen to know of their own family histories.

His interests were broad, varied and widespread, but he developed an enviable skill in being able to keep many windows open simultaneously.

In mid-2024 Horace’s health took a significant turn for the worse and he faced new challenges. Using all his knowledge and experience, he organised much of his forthcoming healthcare and treatment. He was admitted to the Ulster Hospital on November 21, seriously ill. After intensive treatment, in late December he was relocated to Silverbirch Lodge Nursing Home, where he spent his final days.

Horace was laid to rest on Wednesday, March, 5, in the family plot at Magheradroll Parish Church. A Service of Thanksgiving was held afterwards in Ballynahinch Methodist Church, conducted by the Rev Leah McKibben. Personal tributes were delivered by fellow historian Mr Ken Dawson, long standing friend Mr Jim Wells, and his brother, Mr Colin Reid.

The large attendance included his family, numerous work colleagues, history colleagues, friends and neighbours.

Horace Reid was a remarkable force of nature. Despite disabilities and difficulties which would have beaten most mortals, he repeatedly refused to be defeated, meeting each challenge head on and turning them to advantage.

His thirst for knowledge and his enthusiasm for study, for medicine, for history, and for teaching and communicating, were undiminished to the end.